*EDIT* Woo! I just passed 20,000 views on my blog with this post! Thank you all so very much for your support!

|

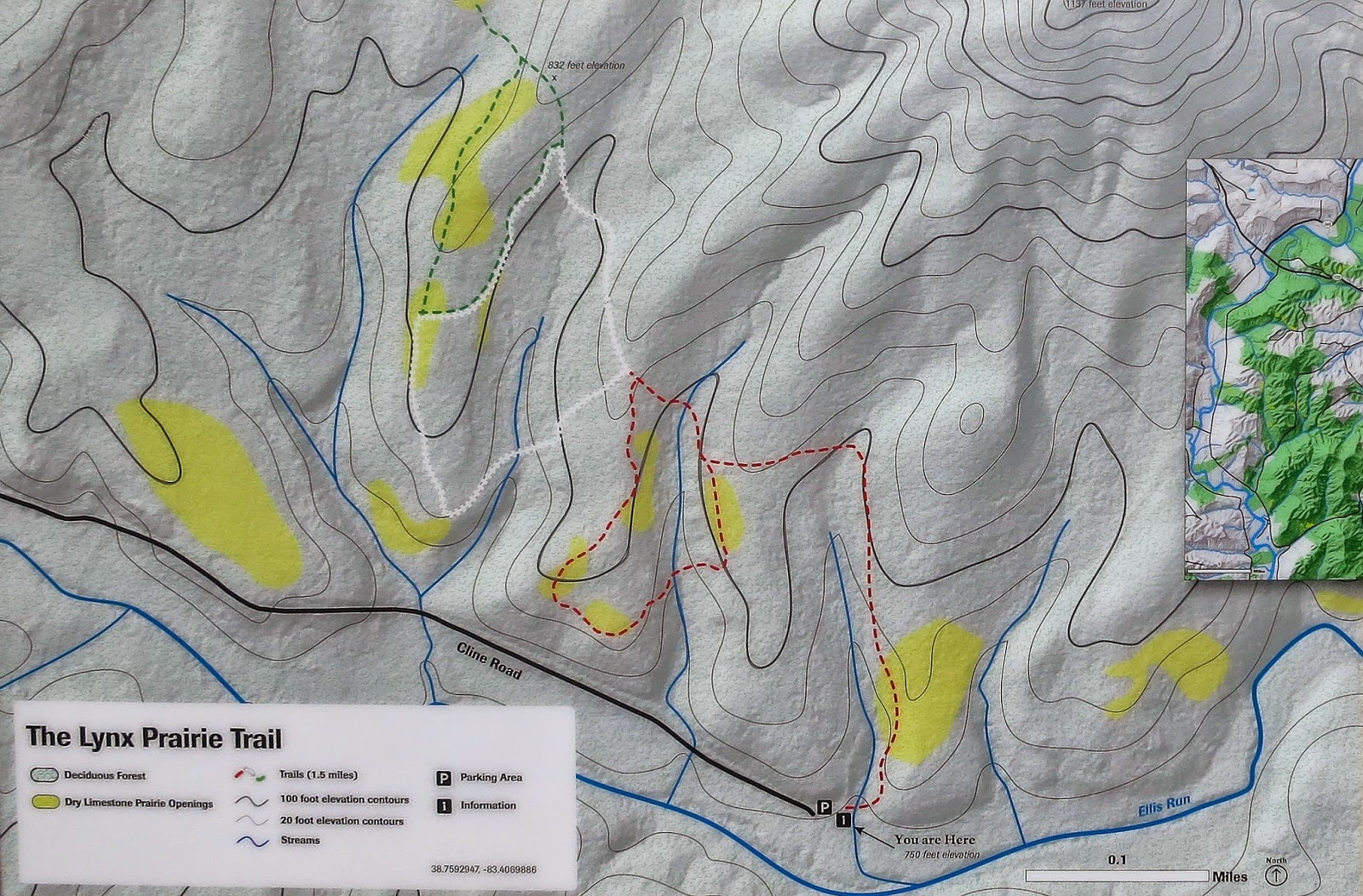

| The North Prairie at Lynx Prairie. |

Let's start with a rarity in Ohio. This is American Bluehearts, Buchnera Americana. This is state-listed as Threatened in Ohio, and is state-listed in many other states as well. American Bluehearts have only been recorded in 6 counties here in Ohio; however, only three counties have had records since 1980. Those three counties are Pike, Jackson, and Adams. American Bluehearts can be found in limestone glades (the one above was found at Lynx Prairie), prairies, open woods, and moist sandy soils like you might find on roadsides. According to ODNR, management is a necessity for this species to continue to exist in Ohio. American Bluehearts are yet another species that greatly benefit from the burning of land every few years. As a result, controlled burning should be carried out in the lands where this species grows to maintain a decent population there. I have covered parasitic plants on here before (Indian Pipe and Squawroot), and now I can also add American Bluehearts to that list. American Bluehearts are what is known as "hemiparasitic," which means that while they can live independently, they can also live as parasites. In the case of American Bluehearts, this species will attach parasitic roots to nearby trees and take nutrients from them, especially when there are difficult living conditions, like a drought, going on.

Let's continue with another flashy flower, Canada Lily, Lilium canadense. This individual was found at Chaparral Prairie and let me tell you, you will not pass by this flower without noticing it. A tall species, Canada Lily can reach heights of 5 feet or so. Hanging reddish flowers 5 feet in the air are hard to ignore. I will admit I was very excited to finally find this plant.

While Canada Lily is showy when you look at it at the angle in the previous photo, look up into the flowers and you'll be blown away. Canada Lily is probably Ohio's most common lily species. A resident of the Allegheny Plateau of eastern Ohio, this species can be found in open woodland, openings in forests, moist prairies, and savannas.

Next let's move on to one of the Liatris species that was just beginning to bloom in the prairies of Chaparral Prairie SNP. This is Dense Blazingstar, Liatris spicata. Dense Blazingstar is the most common blazingstar species in Ohio (there are 7 native species). The individual above was the one that was most in-bloom at the time, as all the others only had about 10 or less of the flowers blooming. When blooming peaks, Chaparral Prairie is awash with tall purple spikes swaying in the breezing among the greens of the grasses and Prairie Docks. Dense Blazingstar is a species that prefers more moist (instead of dry) soils and as a result isn't limited in habitat choices. You can find this species in moist prairies, wetlands like fens and marshes, and other wet fields. Even though this is the most common blazingstar species in Ohio, it's still not overly common by any means. It has been recorded in about 27 or so counties that are scattered all throughout Ohio.

Another Liatris species in bloom currently is Scaly Blazingstar, Liatris squarrosa, which I've previously covered. Another state-listed species, Scaly Blazingstar was blooming in force at Lynx Prairie. You can read more about this species on my Scaly Blazingstar feature.

A very common species in Ohio's prairies is Gray-Headed Coneflower, Ratidiba pinnata. Both Purple and Gray-Headed Coneflowers can be found in Ohio prairies, but in my experience the Gray-Headed Coneflower generally outnumbers the Purple. Notice the drooping yellow petals, a diagnostic feature. A taller species that can reach heights of 3-4 feet, Gray-Headed Coneflowers offered a nice contrast to the low greens of Lynx Prairie as their yellow flowers jutted up into the sky. Gray-Headed Coneflower is an inhabitant of prairies, forest edges, thickets, and railroad right-of-ways. A hardy species, Gray-Headed Coneflower can thrive in both xeric (dry) and mesic (moist) environments. This species can generally be found in the western, glaciated parts of Ohio, but has also been recorded in eastern counties like Athens County.

While Gray-Headed Coneflower is a common flower in Ohio prairies, a rare denizen of the Ohio prairies is Rattlesnake Master, Eryngium yuccifolium. This species is one that is more commonly found in the tall grass prairies of the west and south. In Ohio this species is state-listed as "Potentially Threatened" and according to ODNR has only been recorded in 6 counties here (although BONAP has more counties listed...). The flowers of Rattlesnake Master are unmistakable if you do come across one though, so there's no doubting you found one if you know what they look like. I love Rattlesnake Master and it's always a treat to come across. Chaparral Prairie SNP has the largest population in the state if you're wanting to see some for sure.

The leaves of Rattlesnake Master are an interesting aspect of the plant; they almost look like some sort of agave. Notice the small spines lining the edges. The curious name "Rattlesnake Master" comes from the plant's ability to control a rattlesnake if a human brandishes one of the flowers to the rattlesnake... Just kidding. In all seriousness, the name comes from its historical use by Native Americans to treat rattlesnake bites; however, as one might guess this treatment was ineffective.

A common flower dotting the pocket prairies at Lynx Prairie is the brilliant Rose Pink, Sabatia angularis. Rose Pink (you might also see the name as Rosepink) is a flower of prairies, rocky open woods, roadsides, glades, thickets, and fields. In Ohio this species is found predominantly in the eastern and southern portions of the state. Look for this beautiful species blooming in July to August.

Another common flower at Lynx Prairie was the small, but attention-grabbing, Common Self Heal, Prunella vulgaris. This species is by no means a prairie-only flower. In fact, this incredibly common species has been recorded in basically every single county in Ohio. You can find this flower in a variety of habitats including waste areas, edges of forests, fields, and the likes. The nativity of this species is questionable. There are different varieties of this species, and a few of those are considered native. However, other varieties are from Eurasia and have been introduced here. As a result, a close look by trained eyes can help determine if an individual is probably native or not. I, however, am not a trained eye, so I have no idea if this is a native or foreign strand. Regardless, this is a very attractive flower. Normally the ones I run across only have a few flowers on them as the others haven't bloomed yet or have fallen off. This individual had the fullest bloom I've ever seen in Common Self Heal.

Another common flower at Chaparral Prairie SNP was the Partridge Pea, Chamaecrista fasciculate. Notice the four petals with red center. Also notice the Honey-Locust-like leaves. This species almost looks like the tiny sapling of a locust tree in my opinion. Like many prairie species, Partridge Pea benefits greatly from a prairie fire every few years. After an area is burned, this species can be found in great numbers and generally decreases in number every year after until the area is burned again. This is a species that loves disturbed areas, dry and moist prairies, roadsides, savannas, and other similar habitats. Partridge Pea has been recorded in about 30 or so counties here in Ohio. It's mainly found in the southern counties and seems to follow Ohio River tributaries (like the Scioto River) northward.

These are only a handful of the flowers we came across while in Adams County, but to add them all would make for a massive post. There are more posts to come based around Adams County, but I also have a post on Gallagher Fen SNP in the works and a few others, so stay tuned!