Just warning you now, this is going to be a really long post because not only do I love this preserve, but its history, geology, and flora are simply too incredible to ignore.

Lynx Prairie is a public nature preserve that is a part of the greater Edge of Appalachia Preserve owned by The Nature Conservancy. This preserve is located right outside of the very tiny village of Lynx, OH. Since the last time I've been down, the Nature Conservancy has changed the preserve a bit. There's now a new entrance on Cline Rd. complete with their own parking lot, and a new trail that leads to the other trails from that parking lot. Previously (and you still can), one would park at a small church off Tulip Rd. and walk through the cemetery shown above. The new directions can be found on the Nature Conservancy's page for Lynx Prairie located here.

We weren't aware of the new entrance (we actually got lost and stumbled upon it by accident), so we did the usual park at the church, walk to the cemetery, and appear at the entrance pictured above. On our visit it was going between sprinkling and outright raining with short periods of nothing in between. As a result I ended up using my small Canon point-and-shoot to take many of these photos. I wasn't overly happy with the results (many were washed out), but they're better than nothing. Anyway, on to the preserve itself...

After entering, you find yourself on a small trail winding through a typical forest of the area. But wait a minute, you might ask. This is called Lynx Prairie. Where's the tall grasses? The wide open spaces? Well, these prairies are a bit different than your average prairie.

As you round a corner on the trail, the forest melts away and you suddenly find yourself in an open space; however, this still doesn't look like the prairies most people think of. Before I get into the specifics of the Lynx Prairie complex, let me go over the three broad types of prairies. There are tall grass prairies, mixed grass prairies, and short grass prairies. Tall grass prairies are normally 5-7 feet tall and occasionally reach heights approaching 10 feet. The prairies at Lynx are short grass prairies, but are not overly like the normal short grass prairies of the West.

|

| Part of the extensive Elizabeth's Prairie, the largest at Lynx Prairie. |

So what causes these pocket prairies to form? The answer lies in the photo above. That rock ledge is made of Peebles Dolomite, a type of sedimentary rock from the Silurian Period (443.4–419.2 million years ago). Most of the times the bedrock in Ohio is many feet underground which allows trees to take root and grow. However, in certain places of Adams Co., as in the case of Lynx Prairie, this Peebles Dolomite bedrock actually comes within 4 or so inches of the surface or even breaks the surface itself. This creates a shallow, harsh soil layer. As a result, most trees cannot take root and other short plant species take over. It's worth noting that the name "cedar glade" comes from the fact that Eastern Red Cedars can many times find a small crack in the bedrock and take root, and many times this leads to some of the only trees in the actual glades.

The photo above shows just how harsh the soil is. Pebbles are everywhere in the orange-red alkaline (pH of 8.5+) soil. This poor soil has a lack of nutrients and ends up being very dry due to the water evaporating quickly, which is why this is also called a xeric (or dry) limestone prairie. These factors make it very hard for plants to grow and thrive, and as a result many unique plants have evolved to be able to cope with such a harsh environment. It is thought these pocket prairies in Adams County are older than the last glaciation which ended about 10,000 years ago. As a result, plants have had a lot of time to evolve adaptions for this environment. Many of these plants are rare as they can only be found in cedar glades, which are rare to begin with.

While I'm on the subject of Peebles Dolomite and its effects on the prairies, I want to go over one of the more interesting plants I found growing on Annette's Rock, a good size boulder of Peebles Dolomite in one of the larger prairies. This interesting bluish-green plant is Smooth Cliffbrake, Pellaea glabella. Smooth Cliffbrake - which gains its name from its smooth, not hairy, stem - is actually a species of fern, although it doesn't overly look like a stereotypical fern. This species is epipetric, which means it grows on rocks (as you can see). Smooth Cliffbrake isn't overly a common species here, as it's only been recorded in about 20 counties. It grows on well-weathered limestone, so it is limited to exposed ledges, cliffs, boulders, and the like.

As many of you probably know, wildfires can be a good, even necessary, event for many various habitats. These pocket prairies are no different. Slowly, the woody plants of the surrounding forest begin to gain footholds on the edges and erode the bedrock; this is normal succession. Given enough time, these prairies will shrink and shrink as cedar trees do their work and the forest moves in. So, why hasn't that happened in the past 10,000 years? The simple answer is fire.

|

| The North entrance of Elizabeth's Prairie. Look for Annette's Rock (not pictured) in this prairie. Notice the shrubs/small trees on the left boundary. |

At Lynx Prairie, the trails are set up into three loops built on each other. The trails will take you through the forest and into the prairies. The forest is very open in many places, like in the photo above. Oaks dominate most of the forest, but there are also Virginia Pines, Tuliptrees, and assorted other species.

Of course, Lynx Prairie is filled with wildflowers. The one shown above is the threatened American Bluehearts, Buchnera americana. Other wildflowers found at Lynx include Green Milkweed, Butterflyweed, Scaly Blazingstar, Shooting Star, Garden Phlox, Pale-Spiked Lobelia, Prairie Dock, Gray-Headed Coneflower, Purple Coneflower, Rattlesnake Master, Rose Pink, Self Heal, a few ladies' tresses orchids, Western Sunflower, Whorled Rosinweed, Crested Coralroot, and many, many more. I'll be covering a few of these species in my next post, so stay tuned!

There are many grasses that call Lynx Prairie home. Big Bluestem, Little Bluestem, and Indian Grass are the main species. However, the patch of grass above caught my eye. I came across this patch in a more forested part of the preserve. Upon taking a closer look I was met with a familiar sight...

At the ends of the grass were these flat, attractive spikelets. I knew I had seen these somewhere previously, and it suddenly clicked that this species grows out in the front flowerbed of my mom's house. It turns out that this is Woodoats (also known as Inland Sea Oats), Chasmanthium latifolium. Woodoat is actually a southern species of grass with its northern range lying in southwest Ohio. It's only been recorded in about 9 counties here, which makes it an uncommon/rare plant in Ohio. However, it can be locally abundant where it is found, as is the case at Lynx Prairie. It can be found in moist, shaded woodlands (as in the case of Lynx Prairie) and the likes.

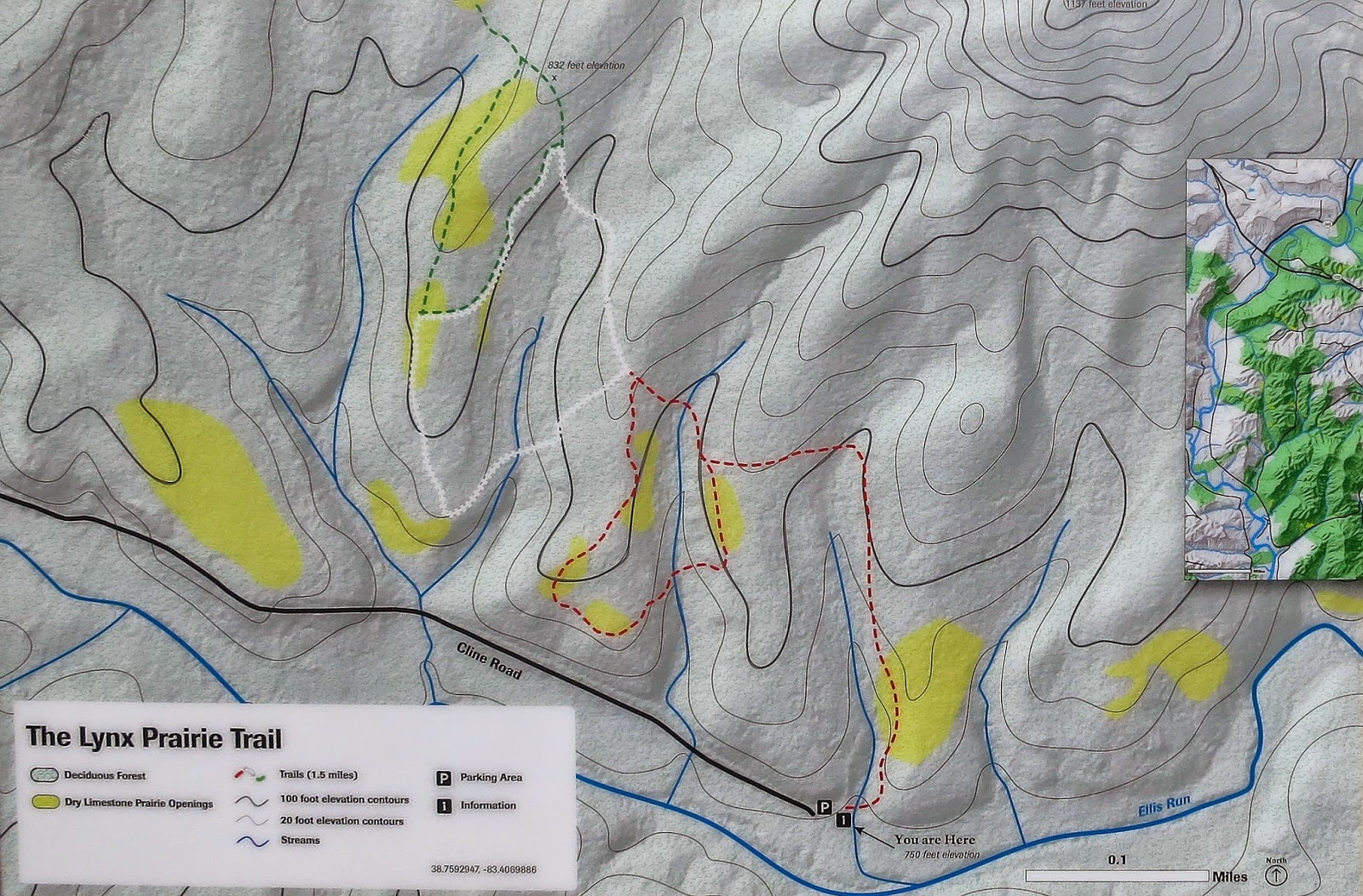

As I mentioned before, there are three loops at Lynx Prairie that one can hike. This is a new, updated map of the preserve that shows the new parking area along Cline Road that was completed in 2014, as well as the new connecter path from the parking lot to the red, white, and green loops. There are a total of 1.3 miles of trails currently.

Lynx Prairie in Adams County is one of the natural gems of Ohio. Containing a system of rare cedar glades, there have been over 600 plant species recorded on the preserve, many of which are rare. This preserve is so significant that it was designated as a National Natural Landmark by the National Park Service in 1967. If you are at all interested, I highly suggest that you take a trip to this preserve. You will not regret it.

Kyle, I grew up in Brown County (right next door to Adams County). I live in Virginia now, but just came back from visiting my mom back in Brown County. My husband and I hiked Buzzardroost, Wilderness Preserve Trail, and Joan Jones Portman Trail. We had one day left in Ohio and I was torn about whether or not to spend it hiking. I came across this post & the one on Adams County wildflowers. Just had to go check out Lynx Prairie. Loved it so much! Just wanted you to know that you inspired us to do one more hike. Look forward to following your blog and to getting ideas for more hikes in Ohio. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for the kind words!

DeleteThanks again Solomon!

ReplyDeleteGreat articles and great layout. Your blog post deserves all of the positive feedback it’s been getting. hikedatabase.com/united-states/hiking-in-rhode-island/

ReplyDeleteKyle, that was an excellent read, good info to know. My good friend just bought 20 acres adjacent the the park. Property is on tulip and touches the cemetery. I am in landscaping and looking forward in exploring these rare plants, including the northern cedar. I would love to have a conversation. We have big ideas for the property. Scottmgiff@gmail.com

ReplyDelete