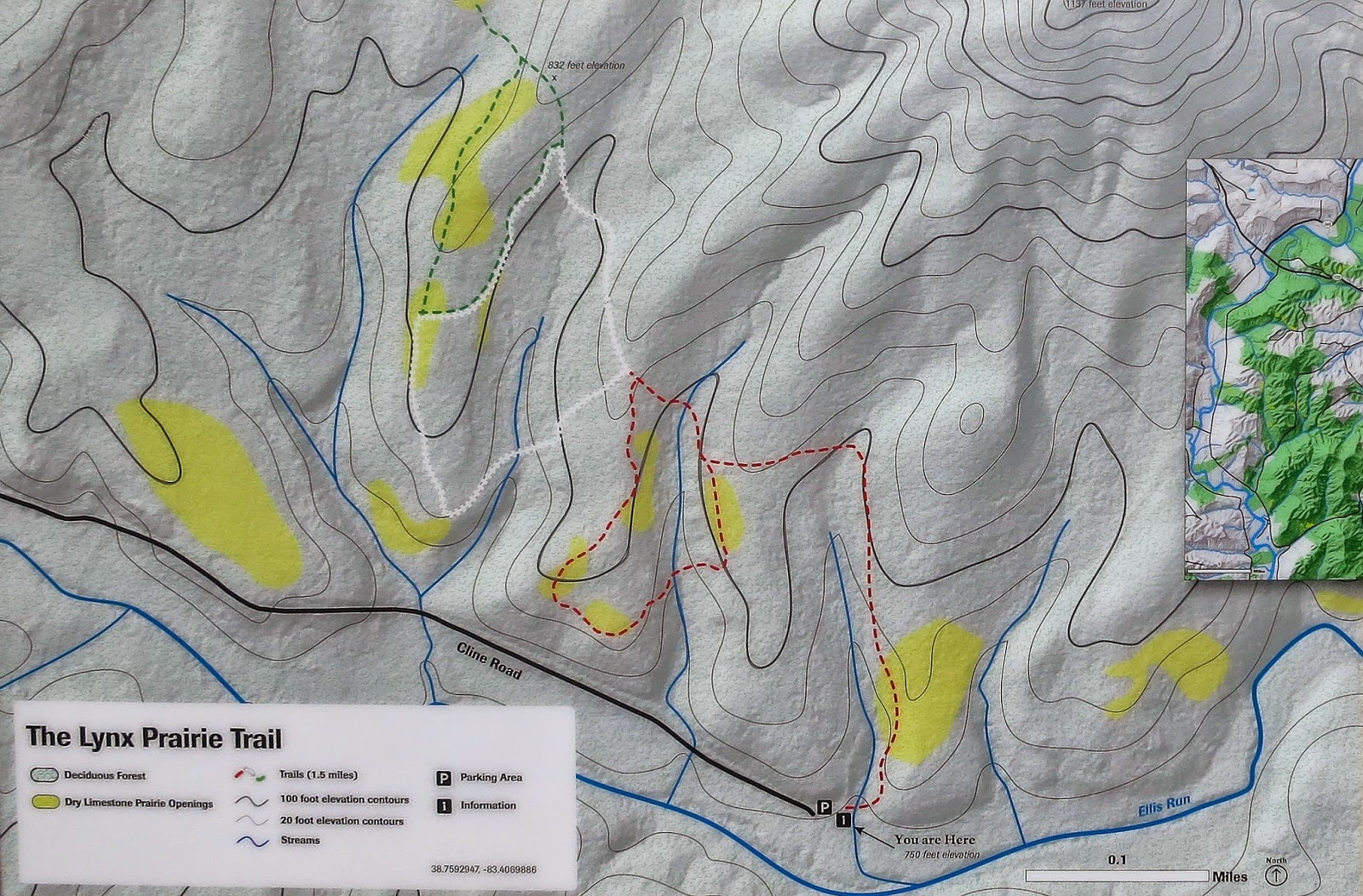

Out of the several places we traveled to, the favorite was Lynx Prairie. Lynx Prairie is a public preserve that is owned by The Nature Conservancy, and is a location I've written about extensively on this blog. To get a general overview about the nature and history of this famous preserve, check out this link: Lynx Prairie Posts. Lynx Prairie is a system of 10 xeric short grass prairies that are of varying sizes. There is a whole host of interesting and rare species that call these "pocket prairies" home, and so I wanted to share a few of the highlights from my most recent trip!

I'll begin with this inconspicuous flower. This is Slender Ladies'-Tresses (Spiranthes lacera). The ladies'-tresses is a group of orchids with a white inflorescence that typically inhabit prairies or prairie-like habitats. There are 9 species that can be found in Ohio, with 3 of those species being state-listed. The Slender Ladies'-Tresses is one of the more common of the Spiranthes species in Ohio.

The ladies'-tresses can be a difficult group to identify down to species. To identify a ladies'-tresses, you should first see if the flowers are arranged in a single-spiral (such as the Slender Ladies'-Tresses), or a double spiral (like the Great Plains Ladies'-Tresses). After that, you have to carefully inspect the flowers. There are several single-spiral species that can be found in Adams County, but the flowers of each species differ slightly. The Slender Ladies'-Tresses has a characteristic green labellum (or lip), which can be seen above. If you want to read about some of the other species of ladies'-tresses that can be found in the prairies in Adams County, check out my previous post: Spiranthes Orchids at Blue Jay Barrens.

When this hot, dry period ended around 4,000 years ago, the forests began to recolonize Ohio. False Aloe found itself suddenly restricted to the dry limestone barrens of southwest Ohio, which were already thousands of years old. Originally kept open during the last ice age by megafauna like the Mastodon, these barrens were now being kept open as a result of fires set by the early Native Americans in the region. False Aloe became the dominant plant in some of these limestone barrens, and one European settler from the early 1800's even made reference to an "agave desert" in the Adams County region. Once the European settlers killed and pushed the Native Americans out of this region, the human-set fires in the prairies and forests of this region ceased and became a thing of the past.

As the 1900's approached, the people living in this region allowed the forest—which had been all but clearcut in the mid 1800's—to come back. The remaining limestone barrens of Adams County that had not been developed or otherwise destroyed began experiencing the effects of natural succession. Red Cedars and Tuliptrees—which had previously been kept at bay by the fires the Native Americans had set for thousands of years—began pushing their way into the barrens. As many of these barrens became forested, the False Aloe found itself dying out in Ohio. Nowadays this species is found in only a few of the protected barrens which are managed with prescribed burns. Sadly, a recent study found that many of the remaining populations of False Aloe in Adams County are reproductively isolated and inbred. This will only lead to a further decrease in numbers over the next century, as the seeds of inbred False Aloe tend not to thrive. At its current state, the future of the False Aloe in Ohio seems rather grim...

Moving aside from the doom and gloom to something more upbeat, here is a recently-hatched Eastern Fence Lizard (Sceloporus undulatus) that Alayna found hiding under a loose rock. Learning that Ohio has lizards may come as a surprise to many, but Ohio is indeed home to 5 species (Eastern Fence Lizard, Common Five-Lined Skink, Broad-Headed Skink, Little Brown Skink, and the non-native Common Wall Lizard). The Eastern Fence Lizard belongs to the genus Sceloporus, which are collectively known as the "spiny lizards." The Eastern Fence Lizard is the only spiny lizard that can be found in Ohio, where it inhabits the southern and southeastern portions of the state.

|

| Alayna Tokash (Master's student in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Ohio University) studies the tiny Eastern Fence Lizard as it perches on Olivia Brooks's (Undergraduate majoring in Wildlife and Conservation Biology at Ohio University) thumb. |

Only an hour later, I came across another baby lizard that was hanging out in a patch of forest between two of the pocket prairies. This is a recently-hatched Common Five-Lined Skink (Plestiodon fasciatus). The Five-Lined Skink is the most widespread and common lizard in Ohio, but isn't commonly seen due to its secretive nature. Five-Lined Skinks can be incredibly skittish, and they will often dart up a tree, under a log, or under the leaf litter upon seeing a human or other potential threat approach. The Five-Lined Skink, along with most other species of lizards, has another line of defense in addition to great evasion skills. The Five-Lined Skink is able to detach its tail in times of danger. If a predator gets too close, or if a predator grabs onto the skink's tail, the skink is able to willingly detach its tail at one of the several breakage points along the tail.

When the tail becomes detached, it begins to wildly thrash about, which—if all goes according to plan—will surprise and distract the predator, giving enough time for the skink to run away. The Five-Lined Skink that I caught had already used this defense earlier in the summer, as can be told by the healing stub of a tail. Amazingly, Five-Lined Skinks, and other tail-dropping lizards, are able to regrow their tail over time. The catch: they aren't able to regrow the bones in the tail, and are only able to grow a rod of cartilage that takes the place of the bones.

Lynx Prairie is a great location for Five-Lined Skinks. The Five-Lined Skink exploits edge habitats, which are areas where two different types of habitats meet. They prefer edge habitats in which a forest meets some sort of disturbed open habitat, especially if such an area offers plenty of rock and log objects to bask on and to hide underneath. There are copious amounts of edge habitat at Lynx Prairie, offering plenty of appropriate areas for Five-Lined Skinks to inhabit.

One of the most unexpected finds at Lynx occurred when Alayna flipped a small piece of wood. Underneath this tiny piece of wood were two Long-Tailed Salamanders (Eurycea longicauda). The Long-Tailed Salamander was something of a nemesis species of mine for the longest time. They can be found throughout Ohio, except for the northwest quarter of the state. They can be relatively common in near streams in moist forests, but they tend to hide pretty well under rocks and logs, and in crevices in the ground. Despite looking for them for several years, the Long-Tailed Salamander evaded me—until this year, that is. This summer I've seen several Long-Tailed Salamanders, with these being number 3 and 4. As their name implies, the Long-Tailed Salamander has an abnormally long tail when compared to other Plethodontid (lungless) salamanders. In fact, a Long-Tailed Salamander's tail makes up approximately ~60% of its entire body length.

Visiting Lynx Prairie always makes for a fantastic day. However, this trip decided to give me two rather unpleasant surprises. Somehow while in the cedar barrens, I managed to pick up dozens and dozens of tick nymphs. In fact, I ended up pulling 87 tick nymphs off my body that day, and also got 40+ chigger bites as well. I guess that's the price you have to pay to see neat things?